Ayça Çubukçu, “On Cosmopolitan Occupations: The Case of the World Tribunal on Iraq,” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 13.3 (2011): 422-442.

Jadaliyya: What made you write this article?

Ayça Çubukçu: The origin of this article goes back to my fieldwork with the global network of activists that constituted the World Tribunal on Iraq from 2003 to 2005. The World Tribunal on Iraq was an experimental project of the global anti-war movement, which emerged in response to the occupation of Iraq by the United States and allies. I say “experimental,” because although civil society tribunals (or, in another parlance, people’s tribunals) had been constituted many times before, the transnational praxis of the World Tribunal on Iraq was unprecedented, consciously experimental, and refreshingly provocative in novel respects.

I was an active participant in the conceptualization and practical formation of the World Tribunal on Iraq, particularly in its early session in New York City (May 2004) and in its culminating session in Istanbul (June 2005). The article is based on this participation, and represents an effort to retrospectively explore competing grammars of legality, justice, and legitimacy imagined by World Tribunal activists in response to the occupation of Iraq. The analysis presented in this article is only a small section of my book manuscript, “Humanity Must Be Defended”: Paradoxes of a Democratic Desire, which addresses—through the praxis of the World Tribunal on Iraq, mainstream NGOs such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as scholars of international relations, political theory, and international law—the entanglement of international law and cosmopolitan human rights ideals with an imperial politics of war.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address?

AÇ: Both the article and the book manuscript it draws from inquire into cosmopolitan politics occasioned by the occupation of Iraq, and aim to magnify the tensions of this politics towards a better understanding of its dilemmas, and, if I may say so, its dangers. While I attend to passionate disagreements, revealing dilemmas, and enabling agreements amongst World Tribunal on Iraq activists in the course of the tribunal’s elaborate constitution and transnational performance, I simultaneously mobilize relevant debates in the fields of political and social theory, international law, and international relations to present a sustained argument for a critical reevaluation of the relationship between law and violence, empire and human rights, cosmopolitan authority and political autonomy.

In the article, I also critique what I call the “instrumentalization thesis of human rights.” When opposing cases of “occupation for liberation,” as in Iraq, promulgators of this thesis typically posit that agents pursuing a distinctly imperial project are insincerely mobilizing cosmopolitan human rights arguments. With few exceptions, the promulgators of this thesis typically proceed to affirm, in contrast, the authenticity of their own commitment to human rights and cosmopolitan solidarity. In my view, posing the problem in these terms—as if it were merely and mainly a question of distinguishing sincere from insincere motivations—prevents us from fully addressing the paradox that the occupation of Iraq was at once proposed and opposed in the name of universal human rights. In brief, the instrumentalization thesis of human rights prevents us from posing certain questions. Within such a framework, for example, it is difficult to account for the particular vitality of the cosmopolitan ethos of human rights in justifying imperial practices, or to address what the particular consequences of this vitality might be. Such questions fail to emerge as proper subjects of interrogation within the instrumentalization thesis of human rights, which tends to occlude a direct confrontation with cosmopolitanism’s constitutive entanglement with imperial politics.

J: How does this work connect to your current research and writing?

AÇ: In both my prior and current work (parts of which appeared in February and March of this year in Jadaliyya as reflections on the Responsibility to Protect doctrine in the case of Libya), I explore a similar set of questions. In the transnational triangle formed by law, politics, and action, I ask: on the threshold between the legal and the legitimate, the law and the exception, what is the foundation, if any, of cosmopolitan politics? By virtue of what ethical ground, and with what perverse effects, have international law and human rights come to monopolize the field of global peace and justice?

With such questions in mind, I have begun to work on my next book project, which participates in a relatively recent yet growing field of inquiry inaugurated by scholars such as Antony Anghie in his book, Imperialism, Sovereignty, and the Making of International Law. More historical in nature, my current work aims to contribute to genealogical examinations that reflect on the constitutive role of imperial practices and legitimation strategies in the formation of international law.

J: Who do you hope will read this piece, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

AÇ: I very much hope that both scholars and activists engaged in work related to human rights and international law will find this article of interest and relevance. This piece attempts to convey some of the complexity and sophistication attending the World Tribunal on Iraq’s praxis, and it takes seriously this sophisticated effort as an illuminating exercise in both political philosophy and transnational solidarity. To the extent that the dilemmas and the challenges faced and negotiated by World Tribunal on Iraq activists in the contemporary minefield of cosmopolitics are symptomatic—which I believe they are—they can offer lessons on the complicated politics of human rights, international law, and cosmopolitanism at the turn of the twenty-first century.

J: Why do you feel that the World Tribunal on Iraq, which was active between 2003 and 2005, is of continuing interest and importance at this moment?

AÇ: First of all, neither the language of human rights and international law, nor the desire to engage in practices of transnational solidarity, is leaving the scene of global politics. If anything, given continuing practices of war and occupation for “liberation,” human rights and international law are only gaining further currency as the language of global politics and solidarity. The praxis and “lessons” of the World Tribunal of Iraq—and I only present my interpretation of them among a multitude of possible others—are of continuing importance because they constitute a critical engagement with the very grammar of this particular language of global peace and justice.

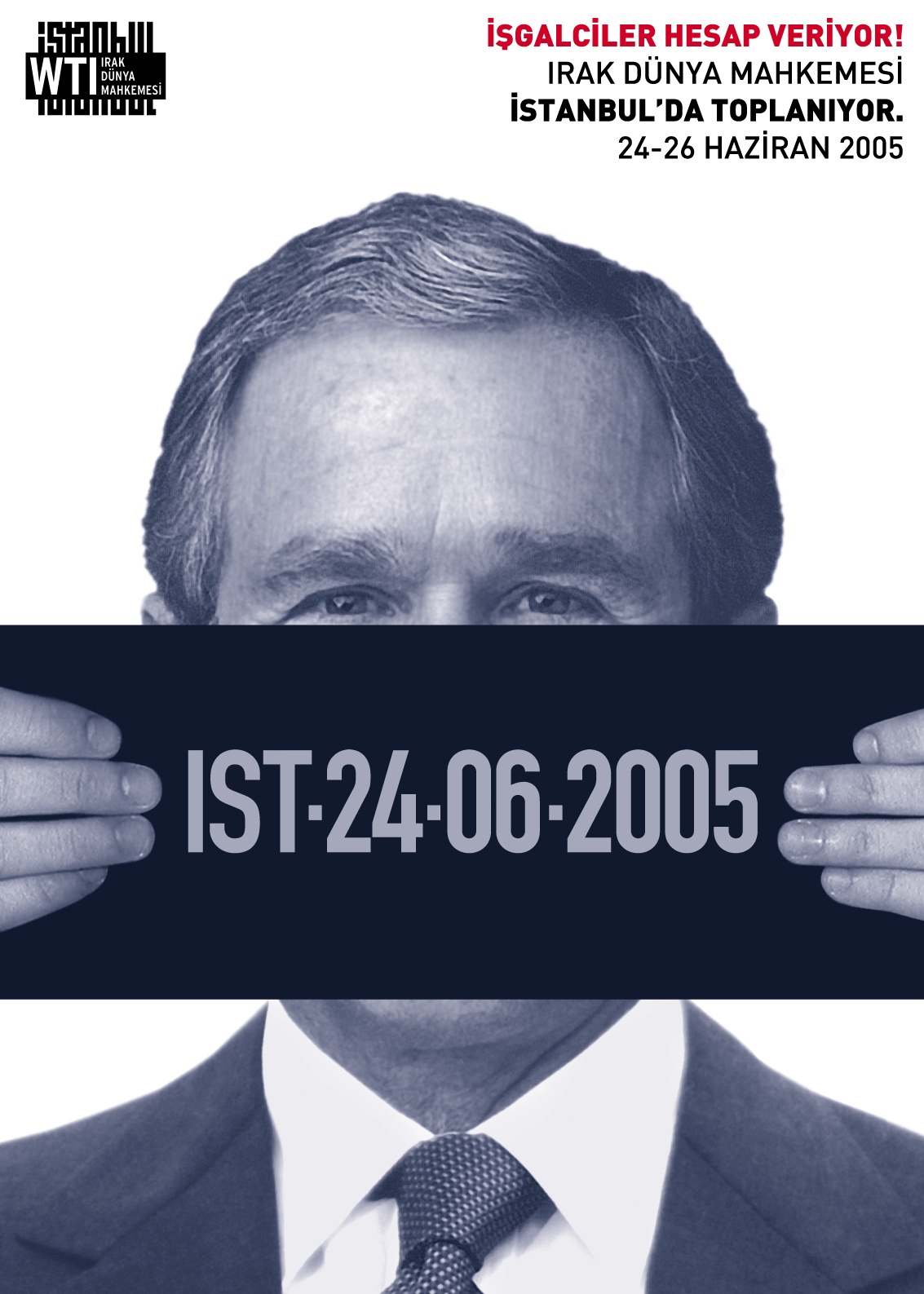

[Poster for the World Tribunal on Iraq`s 2005 session in Istanbul. Image via the author.]

Second, we can expect that the tribunal form will continue to be mobilized by activists in local and global politics. Today, from the Russell Tribunal on Palestine to the Tribunal 12 on migrant rights in Europe, we see proliferating examples of this form. Since the World Tribunal on Iraq was also a critical engagement with the tribunal form itself—deconstructing, so to speak, its own employment of this form in the very act of making use of it—the particular experiment that it presents can be of continuing importance for activists mobilizing this form as well.

[Note: In October 2011, one of the principal organizers of the World Tribunal on Iraq in Istanbul, Ayse Berktay (Hacimirzaoglu)—a renowned translator, researcher, and global peace and justice activist—was taken by the police from her home in Istanbul at five o’clock in the morning. She was subsequently arrested as part of the so-called “KCK operations” carried out in Turkey by Prime Minister Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party for the past two years. While Ayse Berktay still remains in prison for the foreseeable future, she is only one among thousands of intellectuals and activists who have been imprisoned and silenced—such as Professor Busra Ersanli and renowned publisher Ragip Zarakolu—in the last two years. Readers should be aware of an international petition demanding their immediate release, and an end to the recent wave of arbitrary detentions in Turkey.]

Excerpt from “On Cosmopolitan Occupations”:

I would like to address finally the debate concerning the WTI’s own legitimacy at its founding meeting in October 2003. It was at this meeting that the endeavor articulated its name, tasks, and form of organization, as well as the “sources” of its legitimacy. On a global terrain, the WTI’s founding event, as all constituting practices (including the recent one in Iraq), raises theoretical questions about authorization and authority, rights and entitlements, representation and imputation. The participants at this gathering—from Jerusalem and Stockholm, Tokyo and Tunisia, New York and Bangkok, London and Izmir, Copenhagen and Genoa, from Brussels, Hiroshima, and Baghdad—had travelled to the three-day meeting in Istanbul with the singular idea of holding a global civil society tribunal, yet with substantial differences in their respective imaginings of the language the tribunal would speak and the grammar of a justice it would enact.

The outstanding tension operative at the foundation of the WTI was one between—for lack of a better characterization—a “legalist” perspective and a “political” one. While the two tendentious perspectives cut across participants’ professional relations to the law, international lawyers undoubtedly deployed a power-knowledge privilege of “expertise” in articulating the “legalist” perspective with (and over) the “political.” On the one hand, lawyers (and others educated in the universe of international law) often corrected the grammar of the non-lawyer who wished to express “politics” in the tongue of law. On the other hand, something qualitatively different was at stake in the “legalist” position than a desire to proofread clumsy translations of antiwar politics into the language of international law. In the most extreme case, the “legalist” position wished international law to be the exclusive mother-tongue of the nascent WTI, whereby the latter would not only express, but also perceive “facts” through categories of international law—hence recognizing, and thus organizing, reality through the language of law.

According to the legalist perspective, what was perceived to be the self-evident legitimacy of international law would and could be appropriated by the WTI through the adoption of its procedures. If the WTI wished to be legitimate, it was argued, it had to “base itself in the fabric of international law,” while the securing of legitimacy was to be delegated to the expertise of international lawyers as its competent technicians. For the legalist, what would make the WTI a “mock tribunal” was not, as many others thought, a replication, imitation, or mimicking of legal procedures (and the specific roles and language they would assign), but instead the charge that the WTI did not follow them closely enough. Also noteworthy in the legalist perspective was a certain presumption of the claim of international law—in terms of form, substance, and procedure—to universal acceptability. Thus, the legalist position was predicated on the very possibility that the WTI’s findings, if the correct procedural regime was followed, could be something “even the most conservative lawyers or ideologues [could] not refute,” as one participant put it.

In opening the meeting, however, a host from the tribunal committee in Istanbul had introduced a diametrically contrasting vision, shared by many others around the table:

To do this with credibility and legitimacy, we do not need to replicate existing official forms and mechanisms. This is not a theatrical display of how the officially set up courts and tribunals should have acted and decided and operated if they had upheld international law like they are supposed to. This would belittle our endeavor and undermine it….We should keep in mind that many bodies that in procedure and form claim to stick to international law, are in effect condoning its violation.

Instead, the “political perspective” articulated two main bases of legitimacy for the WTI: being a multitude of individuals who were “world citizens” on the one hand, and being a part of the global antiwar movement on the other. First, what was named the “individualist stance” at the meeting asserted an endeavor that was directly global, addressing a political community of global civil society and world citizens. One participant would declare clearly: “personally, I find my legitimacy in myself to start with,” just as she would deduce the WTI’s legitimacy to judge, in the form of a tribunal, from her own sovereign right in relation to a globally constituted political field. The parallel assertion by many participants of the “duty of conscience” of any and all persons, as one foundational principle for constituting a civic tribunal, also falls along these lines, implying, in the words of another, that “we are entitled as any human being part of a world society to protest and take it on ourselves to say to others, this is what should be done.” Deserving attention here is the complementarity between any individual’s “obligation” as an official or otherwise to be held accountable to world citizenry, and any individual’s “right” to judge and ask another to give account in the political field of world citizenship.

In contrast, those who articulated the global antiwar movement as the WTI’s basis of legitimacy found the individualist stance of world citizenship unsatisfactory. Thus, one participant argued, “we can of course refer to our own conscience, but I do not think individuals come first. We do represent something. Otherwise we can say, well my legitimacy is myself—No, I do not think that would make sense.” Rejecting the claim to represent nothing but one’s own autonomous self, one who was able and qualified to pass judgment on and with “the world,” was precisely to reject the position embraced by the individualist stance. But even in the case that those gathered in Istanbul for the founding meeting did “represent” something, the question remained as to what or who it was. Precisely the fact that “the people”—in Iraq and globally—harbored political differences complicated any claim to “representing” or alternatively “being on behalf” of them. In response to this difficulty, one participant stressed: “When we say legitimacy, does legitimacy mean talking on behalf of others? I do not think so…we get legitimacy from the fact that we—I—participated in the protests, all of us participated,” and many others participated.

This position mobilized a powerful critique of the idea of representational legitimacy, while recasting the question on an immanent plane: thus, the legitimacy of action in question would not be constituted by its capacity to represent or speak in the name of an “other” who would structurally remain absent (as the very condition of possibility of such action). Instead, the legitimacy of action would be constituted through the practice of a political subject being “identical” to itself, as it were, or as a manifestation of what the subject already does. Thus, the WTI global network would act with the consciousness of being situated within the global antiwar movement, and performing as a part of it, rather than claiming to act on behalf of it through any representational capacity.

It was this consciousness that resulted in the consequent formulation of a partisan legitimacy specific to the WTI, as distinct from the professed neutrality of official institutions of law. Arundhati Roy offered the clearest formulation of the WTI’s partisan legitimacy in her opening speech as the Spokesperson of the Jury of Conscience:

Before the testimonies begin, I would like to briefly address as straightforwardly as I can a few questions that have been raised about this tribunal. The first is that this tribunal is a kangaroo court. That it represents only one point of view. That it is a prosecution without a defense. That the verdict is a foregone conclusion….Let me say categorically that this tribunal is the defense. It is an act of resistance in itself.

As Roy added, the WTI was an attempt “to document the history of the war not from the point of view of the victors but of the temporarily—and I repeat the word temporarily—vanquished.” Demarcating its amity lines, and positioning itself as an act within the global anti-war movement, the tribunal decided against the pretense to neutral “arbitration in the realm of the ideal” typically instituted by the court-form, as Michel Foucault observed in matters of popular justice.

The “political perspective”—which recognized the need to act in multiple languages and grammars, including the poetic, the artistic and the political, as well as the legal—also argued that the WTI’s legitimacy would be incipient to its founding and was to be earned through action. The tribunal had to actively weave the multiple threads of the global antiwar movement into a constitutive project, instead of simply declaring the “fabric of international law” as providing the basis of its efforts towards performing justice. Yet, if the WTI wished to translate the negative delegitimation of the war on Iraq—as manifest in the global protests of 15 February 2003—into the positive project of a global constituent power, it was difficult to determine the appropriate protocol of translation. Given this difficulty, the idea of accountability was mobilized by WTI organizers to posit on a global political field a primary relationship between a “sovereign” subject of judgment on the one hand, and a “sovereign” subject to be judged, on the other. Theorists of global democracy, Hardt and Negri assert that “with respect to such terms as responsibility, for example, accountability drains the democratic character of representation and makes it a technical operation, posing it in the realm of accounting and bookkeeping.” While this may be true, in the case of the WTI the idea of accountability—or more precisely, the act of holding to account—served, in the first instance, to establish an unmediated, direct relationship between the judging and the judged. Creating what Judith Butler calls “a structure of address” where none had hitherto existed, the WTI would constitute itself publicly precisely on account of asking “the other” to give an account of itself.

It is also necessary to observe, finally, that even after a participant from Baghdad posited it as a distinct issue, at the WTI founding meeting there appeared miniscule specific concern over the legitimacy of the WTI vis-à-vis “the Iraqi people” as such. If, from the legalist perspective, the presumption of the universal legitimacy of “international law” could account for this situation, it is all the more curious in the case of the broad spectrum that I named the political perspective. Minimally, the question did not seriously arise as to the legitimacy of the WTI in the eyes of those from Iraq, even as the resistance in Iraq against the occupation was acknowledged as a “source” of the WTI’s own legitimacy. Thus, as it were, the question of legitimacy was discussed passionately qua ideas of “the world” and “tribunal,” but surprisingly, not that of “Iraq.” Why would this be the case? That the legitimacy problem centered on the constitution of the world (whether politically or legally), I propose, was because “the world” was seen as the greater “community” that was violated by the US-led war on Iraq. The kind of subjectivity that was mobilized in response was one that perceived the war on Iraq as a threat on its own self, a self that in turn was a self-of-the-world. As was expressed by the Declaration of WTI-Istanbul’s Jury of Conscience, “the attack on Iraq is an attack on all of us.” The offended self, moreover, was a “global self”—rather than a national self that was “in solidarity” with another nation or national self. This understanding marks a significant shift from affects of international solidarity, signaling a move away from the solidarity of “fraternal” nationals. The fact that the participants at the WTI’s founding meeting decided to name themselves a “world” tribunal rather than an “international” tribunal bears witness as well to this situation.

[Excerpted from Ayça Çubukçu, “On Cosmopolitan Occupations: The Case of the World Tribunal on Iraq,” Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 13.3 (2011): 422-442. Copyright © 2011 by Taylor & Francis. Excerpted by permission of the author. To view and download the complete article, click here.]